Hussein Elfil died in Khartoum, Sudan, in early July. Memorial texts and messages have been published on Facebook.

Hussein Elfil was my closest friend in Athens, we have known each other since 2011. His experiences taught me what it is like to be a recognized refugee in Greece. He had to rely on himself and he worked as hard as he could and could find work. But he was an old man and to survive he had also to be supported by friends and a relatively well-to-do brother.

He had many friends in Athens and I think one reason was his motto that it is much better to show kindness than anger. Hussein was kind and polite and respectful to other people, a humble man. But I also saw that he, with all his right, could be arrogant and dismissive when he felt badly treated.

He came to Greece as a political refugee in 1999, and he was proud that he received a residence permit and refugee recognition with reference to the Genève convention after just a bit over a year. Most asylum seekers had to wait for many years and very few received a refugee status. I made a good impression, he said, and had explained to the police, among other things, that he was an old man who would much rather have stayed with his family and relatives in Sudan. At that time, it was the police who handled asylum cases.

Most Greeks have known him as Mister Ali. Ali was his “nomme de guerre” as a political opponent of the regime in Sudan and under that name he arrived to Greece.

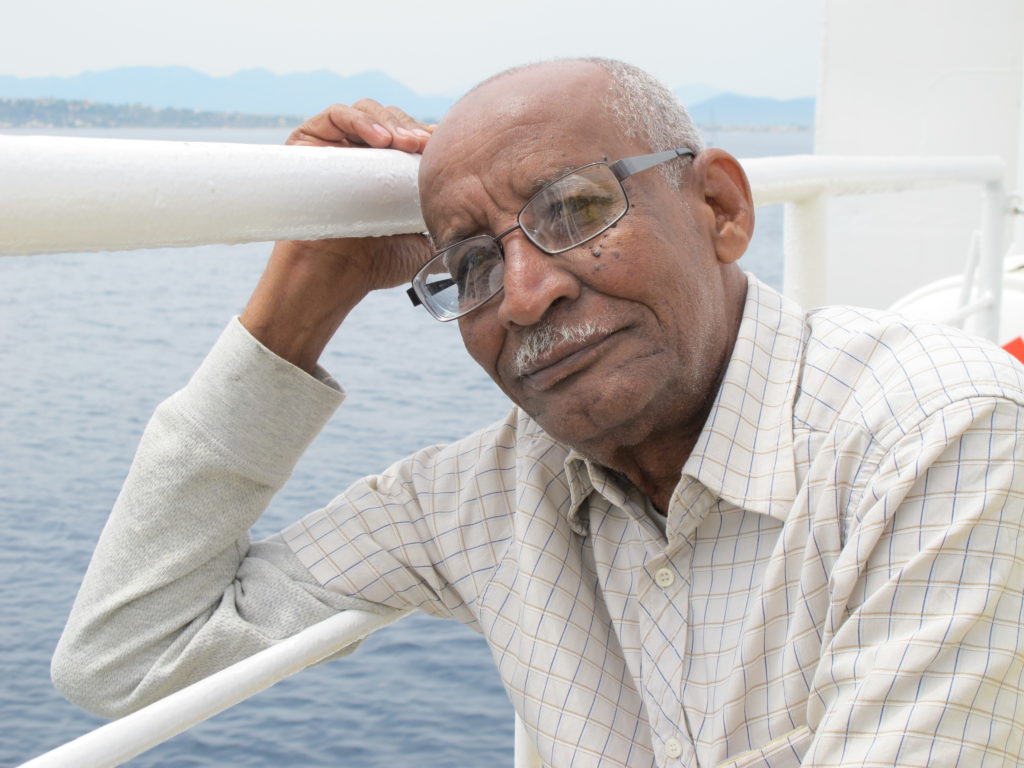

To me, he was at first Mister Ali and later Hussein. I was introduced to him at the Greek-American missionary organization Helping Hands with its premises on Sofokleos street quite close to Omonia Square. It was 2011 and I met a rather tall, slender gray-haired Arab gentleman, extremely friendly and polite, a gentleman at his fingertips, who spoke impeccable English. He looked handsome, and not least he was handsome in his gray winter wool coat, which he received through his friends in Helping Hands.

We had more and more contact, in Athens and over the phone and email. He welcomed me on the phone every time I landed at Athens International Airport. I can still hear inside me his friendly voice saying ”wellcome to Athens, Annette”, or at the beginning ”Misses Annette”. I will never hear this again.

We made excursions

In the autumn of 2013, thanks to him, I came to the closed detention for refugees in Corinth one day. Hussein was our tour guide as he spoke Greek and knew how things work in Greece. But he preferred to speak English.

This visit to the detention in Corinth was a terrible experience in inhumanity for me, I described it briefly in my book Springa på vatten (Running on Water) (2014). There was a photography ban and I could not take pictures. But I remember well the men who mostly were not allowed to go out and more or less hung in clusters in the windows. The premise had been a military base and many Greeks had done their military service here, including the writer and left politician Perikles Korovessis, of whom I rented a home for a time. Also Perikles died this year.

In 2013, the detention in Corinth consisted of a number of large two-storey buildings from the 1930s or 40s. Each was fenced with high bars. Men who had fled from different countries were detained there. If I remember correctly, they were allowed to go out in the small yard for half an hour twice a day. Many were from Afghanistan and I had made contact with one of the men we were to visit. We were allowed to enter the area but not inside the grid. He and I spoke briefly on opposite sides of the grid. Around him stood many other men. He told of about seventy men in each room, bad food, bad clothes, many had neither shoes nor socks, minimal medical care, nothing to do and no one knew how long they would be there. After a while the guards said we had to go and Hussein said firmly that we must obey, otherwise we would get problems.

Greece was in a severe economic crisis, and since the spring of 2012, the government was conservative and dominated by New Democracy, the party that now has government power again. More and more refugees were detained from 2012 and -13. The problems for those who came through Greece to seek asylum in the EU were enormous, not least it was almost impossible to submit their application for asylum. Accepted as an asylum seeker, they received a 6-month temporary residence permit, which was shown by a pink card. Most had no card and had not been able to submit their asylum application. The queues were huge, and the Aliens Police – it was with them that asylum was sought – received applications one morning a week and selected 10-20-30 people out of several hundreds who queued for several days. Most of those who wanted to seek asylum lived undocumented in Greece, waiting for being successful with leaving Greece for other EU countries. Sometimes they were arrested by the police for illegal stay in Greece. Since New Democracy came to power in 2012, the detentions increased and refugees remained in detention for several years instead of being released after a few weeks as before. They were all called “illegal migrants” by the government and by the police.

The conservative government made also statements in media that those in custody would not be released until they agreed to return to their country of original. There were legal defenders for refugees connected to various voluntary organizations, but the need was far greater than the availability of free legal aid.

The largest organization was the Greek Council for Refugees, for which Hussein occasionally worked as an interpreter during his years in Greece. The employment was based on GCR having funded programs, almost the entire business was built on programs, and programs have, as is well known, a fixed beginning and end. It was the same with the other voluntary organizations, the funding was done within the framework of applications for funding programs from major international organizations, the UNHCR and from funds within the EU.

When the left-wing party Syriza won the election in the new year 2015 and formed a government, they released nearly 6,000 detained men from detentions around Greece. Some had lived there for two years under appalling conditions. From the summer, the borders north across western Balkans were largely open and most travelled on, many to Germany.

The detentions are now used by the conservative government – Corinth, Amygdaleza closer to Athens, the detention part at the Aladapon, the Aliens Police in Athens, and elsewhere. This time, the government has said that it will be effective in sending these ”illegal immigrants” quickly out of Greece to Turkey or their home countries. The fact that most of them had a refugee profile was not mentioned.

Hussein accompanied me to the solidarity medical clinic in Athens, in Elleniko, I think it was the spring of 2015. The clinic provided care to Greeks who during the severe economic crisis were without health insurance. Doctors, physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals volunteered here. The medicine came through donations from people around Europe who wanted to support. Without Hussein I would never have found it. The clinic is moving to Glyfada now.

We also mainly enjoyed ourselves, such as a Sunday trip by boat from Piraeus to the island of Aegina, and lunches in the well-known, traditional, tiny down in the cellar restaurant just west of the market square on Athinas street. But Hussein was always small in food and preferred that we had coffee at some simple coffee bar and smoke a cigarette. Sometimes he waited on the street outside the simple hotel where I began to stay, but most of the time we decided to meet outside the Hondas department store at Omonia Square.

He had so many friends

And now he no longer exists, dead in a hereditary blood disease that slowly erodes the skeleton. For more than two years he carried his disease, was treated with chemotherapy at the large Alexandra Hospital in Athens, and initially in Amsterdam where the disease was diagnosed. In Amsterdam, he lived with a nephew in the hope of getting asylum in the Netherlands or at least to have the treatment carried out there. But it did not work because he already had his refugee status in Greece. He had become thin and weak when he left, and just before leaving for Amsterdam we were shopping two pairs of nice Manchester trousers in a shop at Panepistimio so he would be well dressed. At that time he had some money, saved maybe after a couple of years of work for GCR as an interpreter at the reception camps on Chios and Lesvos. Wages were not high, and wages in Greece had fallen sharply at this time due to the crisis and demands from the EU. But I think Hussein was anyhow trying to send money home to his son in Khartoum. Maybe it was mostly like a gesture, because his son Mahid was an adult at this time and had a good job for an international organization.

In the spring and summer of 2020, which were the last months of Hussein’s life, he lived with his sister in Khartoum. She and her husband had plenty of space and their children were grown up and had left. Thanks to the fall of the Sudanese dictatorship in the spring of 2019, he was able to return, and Mahid came to Athens and brought home his father. They were driven to the airport by Hussein’s close friend Themis Sirinides. Who cried in his car back home aware that he would never meet Hussein again.

The good Greek-American missionary couple Themis and Donna Sirinides were Hussein’s main security in Athens for many years. But he was careful not to complain and hang on to them. The couple worked in a Greek evangelical church in Athens and in the missionary organization Helping Hands, and Hussein, who never converted but loved to discuss religion, participated for many years in Bible studies and Bible talks with Themis, and with Scott McCracken, one of the founders of Helping Hands. Scott and his family returned to the United States a few years ago, but their friendship with Hussein lasted. Themis´ and Scott’s families and the people around them were probably Hussein’s main network in Greece. The Greek-Sudanese community, where Hussein as a senior man and political refugee was highly respected, was perhaps just as important. And then he had GCR with its lawyers, interpreters, social workers and others, but if I understand correctly it was more during working hours. He also had close contact with the American social anthropologist Heath Cabbot and helped her in her research studies in Athens 2009-10.

Hussein liked to discuss and was well versed in the Koran and the Bible. He was sceptical of religions, but believed that man is sometimes a weak being and needs an abstract force that backs him and her up. He knew that there are more similarities than differences between what is written in the Bible and the Koran. The message of peace, which Christians usually say Jesus stands for, is also found in the Koran but not quite in the same way, he replied when I asked. The Koran says that you should not attack unless the others attack you. You should not harm anyone else unless they hurt you. And it’s better to forgive than to hurt. I do not defend Islam, but, he added, I claim that I know more than most people here about Islam. The Koran says that killing a single person is like killing all humans. And most Muslims know that, he said.

Hussein told me – about his sixty years before becoming a refugee in Grecce

I had a long interview with Hussein in October and November 2011. That fall I lived in Athens for three months. In the interview, Hussein told about his background in Sudan and growing up in a very famous family. The family was not rich but they lived a very comfortable life, he said. His father was governor of the central bank, his grandfather had been a well-known politician. Hussein joined the communist party as a young man and had many quarrels with his father about it. Communism was a social movement in African countries in the late 1950s and early 60s, he explained. Africa had been colonized and the Soviet Union helped many states to independence.

At the age of 20, he was first imprisoned during a period of military dictatorship but was released after a few days by his father’s actions. In 1969, the army regained power after five years of democracy. He had then left the communist party, among other things, because he did not accept that the leaders acquired precious material benefits. But he continued to be politically active. He was arrested several times during the military dictatorship and eventually emigrated to Saudi Arabia. The military regime was over in 1984 and he returned a couple of years later. The same year the army took power again and this time as a ”fanatical Muslim regime with sharia camps”. Many were executed and many were imprisoned. For ten years he lived in Khartoum ”and it was a very tough time for me”. He was not politically active but was arrested again and again for old activities, about which the military had documents in its archives.

He did not want to talk about the torture, and initially said that he did not mind being interviewed, but without going into certain things.

Life was difficult for me and my family, he said, pointing out that by family he also meant his mother and his brothers and sisters. He had married and the son was born in 1983. She was a very good woman, he said. She had a PhD in English literature, graduated in the United States and is an example of the high position of English in Sudan within that generation. Back in Sudan, she taught English literature until she retired. Later they divorced. Hussein said many times that she was much more educated and smarter than he was. He respected her a lot and when she died a few years after the interview, he mourned her deeply.

How did he support himself during this period of his life? Before traveling to Saudi Arabia, he worked in a bank for many years. Together with a friend, he then started an import business company. They imported goods and materials that the government needed to develop the country, including wood for the shelves for railway construction and engines. In Saudi Arabia, he worked as an interpreter between English and Arabic for the state airline company. He knew English well because Sudan had been an English colony and English education system characterized the Sudanese school system. They learned English in school, and in the bank, everything was in English. Today everything is in Arabic.

He said he was never very successful as an entrepreneur but he did not have financial problems in Sudan. His problems was with the regime and that he was imprisoned countless times. Materially and financially he had a much better life in Sudan than he ever had in Greece.

About Greece

In 1999, he managed to leave Sudan with fake passport and a visa to Greece. Under his own name, he had never been allowed to get a passport. He understood the Greeks as friendly people, knew the climate was good and he wanted to go to Greece. He could have chosen England, and he was there in the 1960s when his sister and her husband were studying there. But England was rainy and the people were not as friendly as the Greeks. Before moving to Saudi Arabia, he had many friends among the Sudanese-Greek community in Khartoum. It does not exist anymore, most Greeks left Sudan during the fundamentalist Sharia dictatorship, and many now live in Australia. The fact that Greece was not so far from Sudan was also a reason. Friends could come and visit – which very few have done since. The son did not get a visa to Greece – but got it in 2020 to bring his father home – and the only time they met during the first ten years in Greece was in Syria. A few years after the interview, they met in Switzerland, where his son was at a conference. Hussein was helped by us friends to be able to travel there.

He was extremely critical of the Greek bureaucracy and all the systemic difficulties he and others in his situation encountered. In the interview, he mentioned a meeting with the UNHCR – the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – which he was called to in 2008 and in which the Greek Foreign Minister participated. We know that Greece is the door to Europe, but Greece is not a big country and has still chosen to be the gatekeeper, he said. The Greek government could have chosen to do as Italy did this spring. They gave travel documents and passports to 18,000 people, who set off for France, which closed the border. Instead of guarding the border, Greece could have done the same. ” (Which Greece did in 2015.)

When Hussein received his residence permit, GCR had an integration program in the form of work where the state paid half the salary. The first job he got was in a fishing company in northern Greece. It was a cold and wet job where he constantly ended up in the water. In the end he gave up, it was not possible to work like that for an almost sixty years old man. In another industry, the sound of a compressor was so loud in the dormitories that it was impossible to sleep. The third job was also within the program, it was with a fruit farm in Crete and his task was to guard the crop and keep the farm clean. Here he liked to stay, sometimes he was invited home for dinner to the owner and he loved apricots and could eat as much as he wanted. In the village next door lived mostly old people and the old women were kind and they called him Mavro, which means black in Greek.

He remembers that time as quite well but quite lonely and eventually he wanted to return to Athens. He was employed by GCR for work as an interpreter and a bit as a social worker at a refugee camp, Bikermi, on the heights above Athens. When the money ran out, the facility closed. Here he became friends with a Russian Refugee family from Uzbekistan, the Stupin family, and they hung out as close friends for many years. Hussein was a bit of a grandfather to the children. The family came to rent a small house with large mold indoor walls near Palini in eastern Athens, and Hussein used to stay here for a few days now and then. He slept on the sofa in their small combined kitchen and living room and the children liked it a lot. He celebrated his seventieth birthday on January 3, 2013 with them. Hussein took me there once. The Stupins had been asylum seekers in Sweden but were Dublin-deported to Greece, where they had arrived on a tourist visa from Uzbekistan’s capital. Their lives as refugees with residence permits meant many years of difficulties, periodically without a necessary work permit because the bureaucracy was unable to provide them with it. Hussein believed that during certain periods they managed to get on with help from their parents in Uzbekistan sending money.

When Bikermi closed, Hussein returned to Athens and worked for the GCR from time to time. Before Bikermi, he had stayed in Sudanese hotels, which were informal hotels where a Sudanese rented an apartment and rented out sleeping places for 3-5 euros a night. After Bikermi, he stayed in Sudanese hotels again, but there were also nights when he slept rough in parks. He had met Scott Mc Cracken at Helping Hands, and they had obtained 200 mattresses, which were distributed to Athens’ Sudanese hotels. Here slept about four to five people per room, resting on mattresses on the floor. (Afghans in Athens had the same system, called Afghan hotels.)

Helping Hands became a fixed point. He knew the staff and he could take showers and wash clothes there. He washed and ironed his clothes at Helping Hands during all the years we met in Athens.

For a few years during his first ten years in Greece, he had double jobs, daytime for GCR and night time as a receptionist at one of Athens’ better hotels. He had become acquainted with the hotel owner who offered him a small accommodation in the hotel. This led him to start working there. Scott at Helping Hands visited him several times there. In 2009 the owner sold the hotel, and Hussein said that this man was a very good man, who came from a very rich Greek family.

His time in Greece as an asylum seeker before he received a residence permit, was not easy. In the beginning he stayed in a hotel and when his money ran out he went to the GCR, which referred him to a shelter for homeless Greeks. It was run by the church and he lived here for three months. He then got a job at a small hotel for six months before he got his residence permit and started working at the fish company.

When we became acquainted, he sometimes helped people with interpretation. For such private work he received 10-15 euros and was often worried that they would not pay him or not pay his subway ticket. He often walked around without money in his pocket. A well-to-do brother sent money when he asked him, but he was embarrassed to ask and tried to avoid it. But when he could not pay the rent and the bills associated with it, he had to. At this time he rented a small apartment in Kipseli, a district just over a kilometre north of Omonia Square, where many Africans live. For kitchen, bathroom and one room with windows slightly lowered from street level, he paid 150 euros a month. I also lived like that when I rented Pericles Korovessi’s small studio. Hussein was almost 70 years old, worked irregularly, had unemployment benefits for a while and was applying for a pension.

Hussein never got a Greek pension. His application took time and in 2016 he started working for GCR again as an interpreter at Chios. I think they hired him because they saw his needs, they knew that he was good, experienced, reliable and that interpreters were needed in the reception camps that arose after the EU agreement with Turkey. He was happy with the job and felt honoured to be employed despite his age – he was 73 years old. He left the apartment in Athens to another Sudanese and moved to Chios and rented a small studio there.

At this time, one could easily be in contact with other countries over telephone cards and apps. He spoke long in the evenings with his relatives in Khartoum, and when one of his close sisters suddenly died, he was deeply sorrow and spoke much of her. Already at this time he thought of possible ways to go to Sudan and meet his big family. But it was risky and the dictatorship was still there.

His last home in Athens – when he was ill and had been forced to leave the interpreting GCR-job that was then on Lesvos – was a small basement apartment just above Platia Kipseli. There he lay ill for months, an unworthy home because it was so cold and damp during the winter and early spring when the electric element was not on. And that was not always the case because electricity is expensive in Greece. Before traveling to Chios, he had a rather nice, simply furnished apartment with a bedroom and living room between Platia Koliatsu and Platia Kipseli, a part of Athens where many Africans live. There I slept two nights on my way from Samos to Stockholm. At this time, the brother regularly sent money to him. Before moving there, he received help with housing through the Evangelical Church in Koukaki and his friend Themis Sirinides. Hussein shared a bedroom, kitchen and bathroom with Mister Adams from South Sudan. They did not go along well, but had to put up with each other’s quirks – two older men. Until the apartment had to be cleaned up due to bed bugs. Hussein moved with joy back to Kipeseli, where he felt at home. Here he went to Sudanese cafes and watched football – which he loved – and to the small restaurants of the Sudanese community at Platia Kouliatsou he had his meals now and then. I think he paid for himself through services in different ways. But most of all, he was content with salad and feta cheese, and that was what was in his rather empty refrigerator.

During his last years in Athens in the damp, pitiful apartment, he had some support from friends within the Sudanese community. Some came to visit him, shop for him, cook for him, help him in the bathroom and take care of his laundry. His friend Themis Sirinides arranged home care, but the help was volunteer-based and seems to have ceased eventually.

I was with him for several hours every afternoon for ten days in Athens in April 2019, and thought he would not live that much longer. He was weak and thin, mostly in bed, did not complain, followed the fall of the dictatorship in Sudan on television alternating with football matches. During these days I met some of his Sudanese friends. He went to scheduled treatment at Alexandra Hospital. I was with him there once. After several months of treatment, he became stronger later in the summer, and spent a couple of months in Amsterdam with his nephew in the autumn. There he received nursing, good food and appetite . He returned to Athens in the New Year 2020 to continue the treatment as planned, was very weak, was hospitalized, his son came traveling, they spent a few weeks in the damp apartment while papers and tickets to Khartoum were arranged, he said goodbye to American, Greek and Sudanese friends and GCR, was driven to the airport by Themis and flew to Khartoum with his son by his side. It was a difficult and tiring journey, he then told me on the phone from Khartoum over Whatsapp. After that we spoke a few times and because I asked and asked, he told me in detail how well he was taken care of in his sister’s home and that his son and his extended family took care of him. From May, he never answered again when I called, and he neither called back nor sent messages.

I miss him so much, as a close friend and a good comrade, and I will feel awful the next time I come to Athens. There are so many places and so many streets associated with Hussein. The whole city is full of memories of Hussein and his warmth and kindness.